Own Your Own Intelligence (OYOI)

Own Your Own Intelligence (OYOI)

Own Your Own Intelligence - - A Discussion Framework

Dr. John Sviokla and Paul Baier, GAI Insights

Draft - Aug 6, 2024

Summary

Generative AI is a powerful technology, and the strength of large technology firms is unprecedented, with their influence continually growing. Sovereign nations, companies, and individuals are understandably concerned.

Own Your Own Intelligence (OYOI) is a broad concept framing the issues involved when nations, organizations, and individuals claim agency over data, process knowledge, and cognitive capabilities. We assert that firms deriving considerable competitive advantage from "Cognitive Guilds" (explained below) must be particularly cautious about sharing process information and data with large technology vendors in this new age of Generative AI.

We hope that framing these issues sparks conversation and action for mitigation steps, more robust technical solutions, industry partnerships, and sensible regulatory and legal changes.

Context and Background

The Industrial Revolution was built on three forms of capital (or assets): natural, human, and financial. The digital revolution created three new forms of capital (see Everson & Sviokla, 2018): behavioral, network, and cognitive (or intelligence).

For the past two decades, countries, companies, and individuals have largely been willing to relinquish their behavioral assets (e.g., location data, preferences, reading habits mined by firms like Facebook) and network assets (e.g., social network and human connection data used by LinkedIn and Instagram) in exchange for free or discounted services. During this time, most market participants – individuals and firms – have lost control of these two assets. All Western countries and allies, except South Korea in social media, have allowed U.S. giants to dominate.

Do You Rely on a Cognitive Guild?

When assessing your firm's cognitive and intelligence assets, it's crucial to reason from first principles about your sources of data, processes, and performance. Generally, low-value-added tasks have been automated in modern organizations. The vast armies of green-eyeshade bookkeepers that once populated banks are long gone, their work having been automated. Tasks that have resisted automation are either low-value-added but difficult to automate (e.g., fast-food workers) or high-value tasks with ambiguity, high knowledge requirements, and cognitive complexity (e.g., high-end legal work or underwriting).

Ask yourself: How much of my firm's competitive advantage relies on highly trained/educated people who have served a long apprenticeship in their field and our firm? If the answer is significant, as in accounting firms, research and development teams, insurance companies, or news organizations, you should be very thoughtful about how deeply you allow vendors to help partially or fully automate your high-value-added cognitive work.

While serious vendors have contracts that allow firms to protect their data and trade secrets, it is much more challenging to safeguard processes and practices that often contain valuable insights. For example, a major U.S. health insurance firm has implemented a GenAI system that records doctor-patient conversations and has vastly improved productivity. The average doctor visit by their providers used to be fourteen minutes: four with the patient and ten on paperwork. With this new system, the average visit has shrunk to seven minutes: six with the patient and one on paperwork. Patient interaction time has increased by 50% while decreasing total time per patient by 50%. Additionally, the firm retains audio files of conversations because new algorithms can diagnose some conditions directly from voice data.

This application uses a GenAI/AI model for voice-to-text data codification and another for interpretation and logic processing in the hospital's system. The voice data itself has value for direct diagnosis with new algorithms that enable the insurance firm to diagnose patients directly from voice files for certain conditions.

We argue that this insurance firm should keep this knowledge proprietary (which they did) because it not only helps competitors understand where to look for value but also provides insight into future potential value, such as capturing diagnostic information in voice files. This exemplifies a firm dedicated to owning its own intelligence.

Understanding How Tacit and Explicit Knowledge Become Emergent Knowledge

In 1961, Michael Polanyi made the important distinction between explicit and tacit knowledge, stating, "We know more than we can tell." Tacit knowledge is deeply ingrained, often intuitive, and typically learned through experience rather than formal instruction. It includes insights, techniques, and processes that are not easily codified or transferred. Explicit knowledge, conversely, is information that can be easily documented, shared, and applied—such as manuals, databases, or formalized processes.

GenAI models gather knowledge and relationships among data using n-dimensional representations of linear algebra and transformer algorithms to effectively navigate this vast search space. In this process, the models create what we call "emergent knowledge," which is emergent in two ways: new knowledge emerges from the vast sea of data input to these models when processed and trained, and it emerges as these models generate new expressions of knowledge through interaction.

From an OYOI perspective, when a firm gathers and processes vast amounts of explicit knowledge (e.g., customer phone calls, diagnostic conversations), which is nominally explicit but functionally tacit due to its sheer volume and disorganization, the LLM creates a model that makes that knowledge more accessible. Patterns and models emerge from this sea of data through tokenization and training.

In the context of cognitive work and intelligence assets, it's crucial to understand that firms possess substantial process knowledge, tacit knowledge, and explicit knowledge that remains "hidden" due to its sheer volume and disorganization. It is vital to assess, before the fact, how valuable this emergent knowledge might become when considering which cognitive assets you want to own.

Generative AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), plays a transformative role in this dynamic by tapping into vast amounts of codified materials and converting implicit relationships into explicit ones. Furthermore, LLMs capture nuanced understandings embedded in text, images, and sounds—previously accessible only to experts—and make them explicit, thereby broadening access to high-level cognitive capabilities.

Consider the health insurance firm example mentioned earlier. The AI system captures and processes doctor-patient conversations, transforming tacit knowledge (the doctor's diagnostic reasoning and conversational cues) combined with explicit knowledge (structured patient data) into emergent knowledge—practical insights on documentation and diagnosis. This not only enhances productivity but also opens up new avenues for innovation, such as using voice data for direct diagnosis. However, this also means that all firms must be vigilant about how this newly emergent knowledge is controlled and utilized.

As firms increasingly rely on LLMs to combine tacit and explicit knowledge at scale, they must carefully consider the implications of making this knowledge emergent. This is where the concept of "owning your own intelligence" becomes critical, as it pertains to controlling not just data and processes, but also the newly codified knowledge that could be pivotal for competitive advantage.

Who are the firms who need to worry the most about Own Your Own Intelligence (OYOI)?

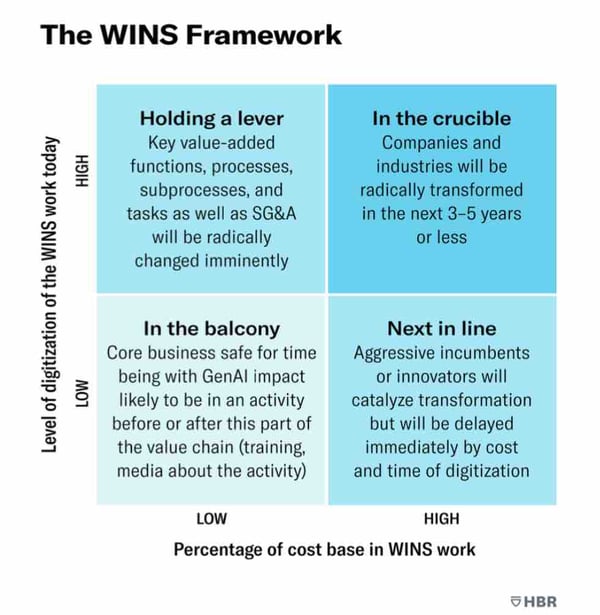

In the September 2023 Harvard Business Review, we introduced the WINS framework (see image below), positing a new subcategory of work that deals with Words, Images, Numbers, and Sounds. If your firm's cost base is largely composed of WINS work and is highly digitized, we believe your firm's core economics could change radically.

Firms that are "in the crucible" or "holding a lever" should be particularly concerned about owning their own intelligence because they likely have many high-value-added cognitive tasks and a comprehensive process of hiring and training people into their "guild." As firms have not traditionally automated this type of work, it's crucial to consider the implications before enabling technology suppliers to codify and scale cognitive work through capturing proprietary data at scale. This creates a new asset which, if effective, radically changes the nature of your economics.

For example, some believe that with new tools such as Harvey for legal work, we will see massively increased labor productivity for lawyers in many tasks. In software programming, task-level productivity improvements range from 20-50%. This new symbiosis of cognitive technology and cognitive guild work will yield radical new economics and capacity in WINS work.

For these reasons, all high-WINS firms should carefully consider what they share and how deeply they need to create internal capabilities to retain control over their most precious data and processes. Additionally, they need to be sufficiently knowledgeable in their domain to understand what they want to buy versus build as this new wave of technology creates the ability to improve or influence some of the most valuable cognitive work and cognitive assets in the entire economy.

Recommended Action Plan

You need to consider three perspectives: business, technological, and legal.

From a business perspective:

Understand how WINS-intensive your business is using the WINS framework. If your business is in the top half of the matrix (either "In the Crucible" or "Holding a Lever"), analyze your critical data, processes, knowledge, and insights. Decide what you're willing to share with outside providers and what you need to keep proprietary.

Determine the depth and breadth of in-house GenAI/AI capability you want. In the 1980s, many money center banks outsourced their core IT systems, but Jamie Dimon, then at BankOne (now part of JP Morgan Chase), kept much of his technology in-house as he saw it as a strategic advantage. Similarly, because cognitive assets are critical to all firms, you must decide how deeply you want your staff and talent to understand and command GenAI/AI capabilities.

Embrace the "Educate, Operate, Transform" model:

- Educate: Ensure top executives have at least 5 hours of hands-on experience with new tools to understand their potential. Train 5-10% of your people deeply enough to progress from prototypes to pilots to production applications.

- Operate: Find practical applications in areas like software programming, customer service, sales, and employee training to gain operational efficiencies and real-world experience.\

- Transform: Reimagine customer experiences and production processes to drive radical new economics and performance.

From a technical perspective:

- Use role- and transaction-based controls when people interact with AI models.

- If operating within known environments like Google's Vertex AI, these controls are in place. For more varied environments, you may need to buy or build your own security layer.

- For firms handling sensitive data, keep considerable amounts behind your own firewall and have clear policies and monitoring on communications with your AI provider.

- Employ third-party tests and controls.

From a legal perspective:

- Consider applicable regulations and jurisdictional policies (e.g., HIPAA for healthcare, GDPR for the EU).

- Ensure contracts clearly articulate data ownership, derived insights, risks, and remedies.

- Implement proper risk controls and audits to minimize second-, third-, or fourth-party risks.

Summary

GenAI/AI is enabling the codification and "ownership" of cognitive assets through new models and their emergent knowledge properties. Now is the time to consider the relative importance of this trend to your firm's economics and competitive position. Given how rapidly these trends are moving, it's vital to think through your strategy and economic approach before opening up your data, processes, and implicit and explicit knowledge to firms with enormous market power and motivations to scale quickly.